by Enrico Spadaro

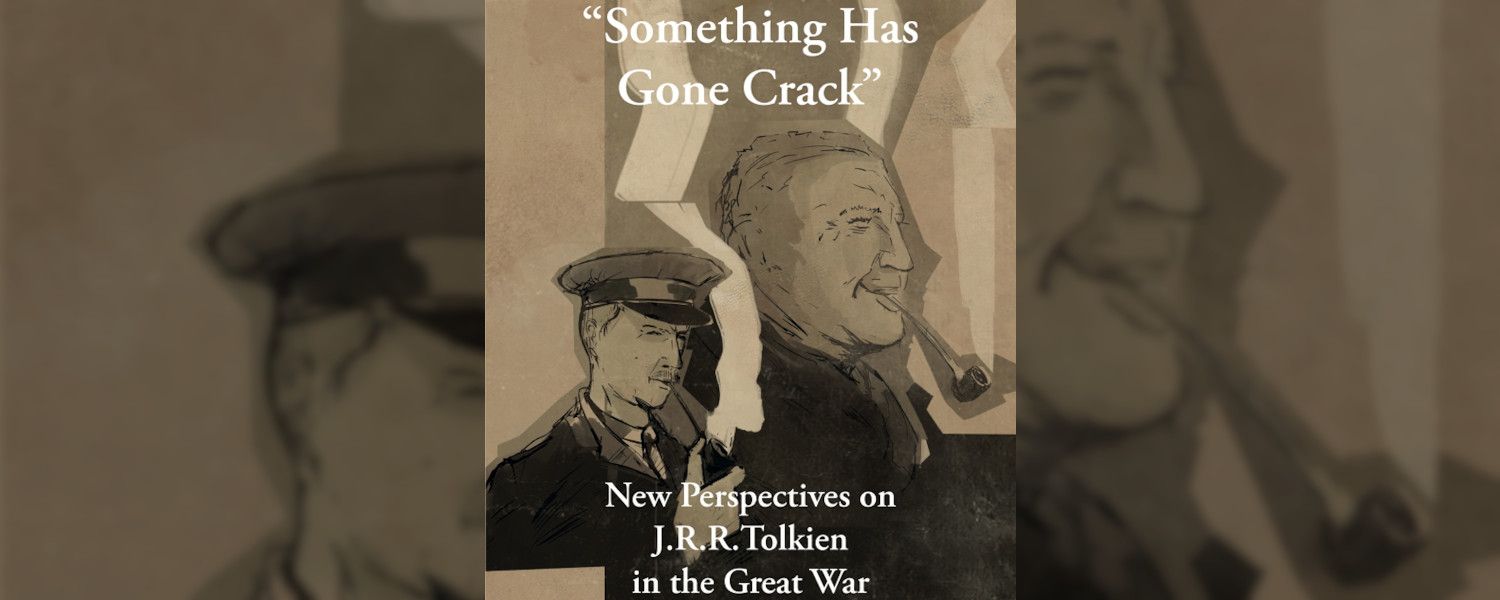

In 2019, the centenary of the conclusion of the First World War was celebrated: Walking Tree Publishers (whom we thank for the free copy they sent us) therefore thought that the times were propitious to commemorate the occasion with a volume focused on Tolkien’s experience as a soldier during the First World War and of course as a war writer. As the editor of the series Cormarë Peter Buchs explains in his acknowledgements, the original idea was to organize an international conference for the anniversary of the Battle of the Somme in 2016, possibly in Northern France where Tolkien had fought. Once this proposal had lapsed, a volume of essays concerning Tolkien and the Great War, edited by Janet Brennan Croft and Annika Röttinger was born. The volume was nominated in the category of “best book” at the Tolkien Society Awards 2020, overcome only by Oronzo Cilli’s publication: Tolkien’s Library.

This is a topic that has already been explored and extensively discussed previously. Croft is a notable scholar in this field, having written the monograph War and the Works of J.R.R. Tolkien and also edited the 2015 collection Baptism of Fire: The Birth of the Modern British Fantastic in World War I. Likewise, Röttinger contributes with her wide experience in military history. The best-known precedent regarding the relationship between Tolkien and the First World War is undoubtedly Tolkien and the Great War (2003) by John Garth, a famous work of erudition and biography which has now become a cornerstone of the biographical studies on Tolkien. While admitting that a new line of studies has now been paved, Croft, in the introduction to the volume, underlines how the topic «is not exhausted at all» and that:

There is still some detective work to be done in discovering facts about [Tolkien’s] service and convalescence; there are themes and motifs still to be examined […]; other works of art or scholarship in other fields may illuminate) aspects of Tolkien’s work that have not yet been fully explored.

The “investigative work” and the careful research method make “Something Has Gone Crack” a highly respected miscellany in the field of Tolkien Studies. While Garth’s biographical work was purely centred on the emotional narrative of Tolkien’s life and relationships, this volume explores a wide variety of minutiae concerning themes of war and historical events, also relating them from aliterary point of view and of “history of the ideas” to Tolkien’s life and work.

The tone is academic and scientific, also thanks to the inclusion of a map of the battle of the Somme and a detailed chronology of Tolkien’s service in the British army. The interest in dates and details, especially for those that seem to characterize the narrative work of Tolkien as a writer or of a painter like Niggle: it could perhaps make the reading of the articles a less engaging experience for the common reader, but it becomes an element of great value to the researcher.

Contents

The volume is divided into four sections. The first, about the “Conduction of the war”, examines the similarities between the Great War and the various battles in Middle-earth. The second section focuses on the new applications of Great War research applied to Tolkien’s biography. The third section focuses on the “Roots of the main themes of the Legendarium” that are found in the Great War. The final section looks at the so-called “Otherness”, with a different approach to war and Tolkien’s fiction through less obvious but equally well documented themes, which refer to race, class, gender and sexuality.

The volume exploits many contributions, so perhaps only a few salient aspects might be mentioned. Tom Shippey and John Bourne examine the “steep Learning-Curve”, which the British Army had to face during this period, that is the rapid formation of combat-ready battalions, which led to the “New Army”, composed largely of new and untrained recruits, providing a different and more vivid historical context. Glenn Peterson, in Strategic Blunders in the First Age Great Battles, argues that military service provided Tolkien several elements for creating the epic battles of Middle-earth, with a particular focus on leadership and cooperation between allies.

Tal Tovey’s article on Aspects of Total War hypothesizes that the adventures of the hobbits reflect the historical passage towards “total war”, that is, the passage, even ideological, from the old conflicts between rulers and dynasties, typical of the ancient age, to wars between nations and peoples within Western civilization

Fault Lines Beneath the Crack by John Rosegrant finds its origins in Tolkien’s rather vague statement that «Something has gone crack» following the tragic death of his friend Rob Gilson: what «has gone crack»? The author of the article suggests both a physical and a psychological interpretation that would have caused a real trauma in the young Tolkien.

Michael Flowers’s text on Tolkien in East Yorkshire, (Tolkien in East Yorkshire, 1917-18: A Hemlock Glade, Two Towers, The Houses of Healing and a Beacon by Michael Flowers) attempts to deepen previous researches concerning the period of convalescence passed by Tolkien in that British region. The days spent there by the future Oxford philologist would have influenced the creation of thememorable hemlock glade of the tale of Beren and Lúthien and potentially other allusions to the real world. This article, complete with maps and finely crafted details, was among the nominees for the title of “best article” for the 2020 Tolkien Society Awards.

John Garth attempts to tell a singular and intriguing popular legend that is inspired by Arthur Machen‘s story The Bowmen and the possible points in common with the first attempts made in that period to sketch a mythology by Tolkien. Garth partly takes up some of the essential motifs dealt in his great monograph Tolkien and the Great War and explores a curious episode just mentioned in the 2003 text concerning the “Angels of Mons”, comparing angelic motifs, supernatural interventions, folklore and elements of superstition that, through the aforementioned account of Machen, reappear in the mythical figures outlined byTolkien.

Lynn Schlesinger refutes the concept of World War I as an exclusively male context and investigates the possible role of women in wartime, who ruled and worked in hospitals, drove ambulances, led canteens, and other fundamental tasks parallel to the war aspect. The author reiterates that such duties would have influenced female characters of Tolkien himself.

Felicity Gilbert’s Mighty Men of War disproves previous considerations of gender roles in wartime, illustrating greater fluidity in attributes attributed to men and women, respectively. Giovanni Carmine Costabile, the only Italian author of the collection and independent researcher, concludes the collection by outlining an interesting thematic link between Éowyn and the eighth Scottish Regiment Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders through the work of the Glaswegian painter Frederick A. Farrell. For more details and to find out more, you just have to read the volume.

“Something Has Gone Crack” places itself as an extremely varied and interesting contribution to the field of Tolkienian biographical studies. The constant parallelism between the historical, political and social context of the Great War, the event that shocked the certainties of the modern world, and the genesis of Tolkien’s work represents the strength of this work. Some of the essays may perhaps appear less convincing and meaningful than others in the exposition of the relative theme and it may happen that some topics are more difficult to read but on the whole the volume is quite engaging. All the contributing authors underline Tolkien’s difficulties about biographical studies and, therefore, are intended to develop the discussion rather than sustain some necessary intention or relationship essential to Tolkien himself. The work is aimed at the most hardened and precise fans, but above all, to those scholars and researchers who are interested in biographical studies and in particular in the close relationship between philology and war, between life and literary work, between experiences and ideas. It is therefore a collection that cannot be missing on the shelf of a true Tolkien scholar.