An Interview with John Howe

by Erie Rizzi Neves

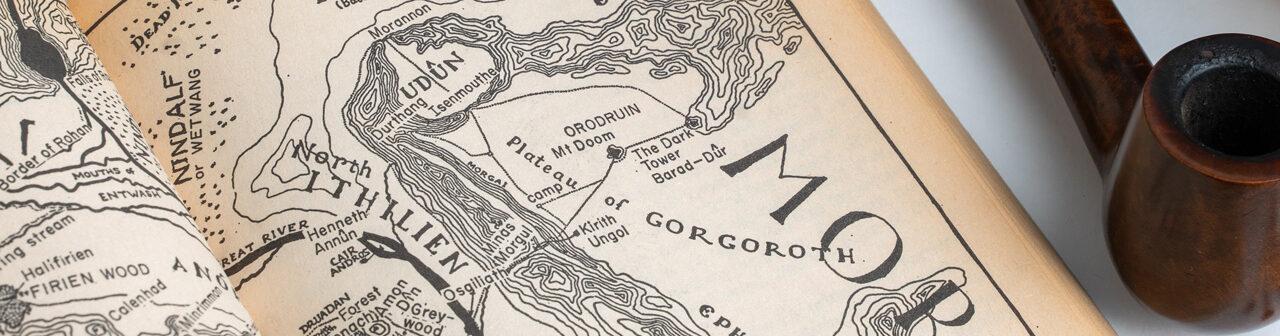

J.R.R. Tolkien has achieved remarkable popularity across the world thanks to his ability to develop a complex and fascinating “legendarium”, which tells the history of Middle-earth from the cosmogony of Eä to the rise of the Fourth Era.

Such fame has been strengthened by Peter Jackson’s trilogy “The Lord of the Rings”, which has had an impressive feedback from both public and critics (it has won in total 17 Oscars), the trilogy of The Hobbit, again by Jackson, and recently with the news of the Amazon Prime series’ production “The Lord of the Rings”, of which very little is known nowadays.

Today, we have the privilege to talk with a legend, a person who has been part of all the aforementioned projects: the Canadian illustrator John Howe.

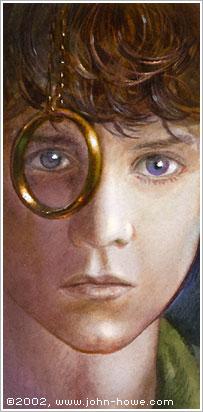

Known worldwide for his illustrations for J.R.R. Tolkien’s works (covers, books, calendars, etc.) and his participation with Alan Lee as designer and concept artist of Jackson’s trilogies, Howe speaks of the films, of art and of his personal and professional experiences with great fondness.

I would like to thank Martina Ravaioli, Maurizio Ieiri, Sebastiano Tassinari, Ana Julia Rizzi, Alessandra Trapani, Viviana Mioranza and Alessandra Cois for their important contribution to this project.

Mr. Howe, tell us a little bit about who you are and what your academic, artistic and professional backgrounds are.

I was born and grew up in Western Canada, and came to France to study in 1976. I spent 3 years at the École des Arts Décoratifs in Strasbourg, and have since worked as an independent illustrator.

Many people decide what they want to do when they grow up from an early age, while others choose their vocation only later and others do not find their passion at all. When did you know that art was your world and that you would become an artist?

I have always wanted to do something artistic, though it wasn’t until my teens, once I had finished high school, that I decided to pursue further art education. The idea of spending a year in Europe appealed to me. In the end, I never returned to Canada.

Most of the people of my generation had the first approach with J.R.R. Tolkien and his mythology through the section of Dungeons & Dragons, the role playing game. Later the new generations got to know Middle-earth through Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy. When did you have your first contact with Middle-earth and what aspect gave you this spark, this passion so strong that you dedicated a whole life to it?

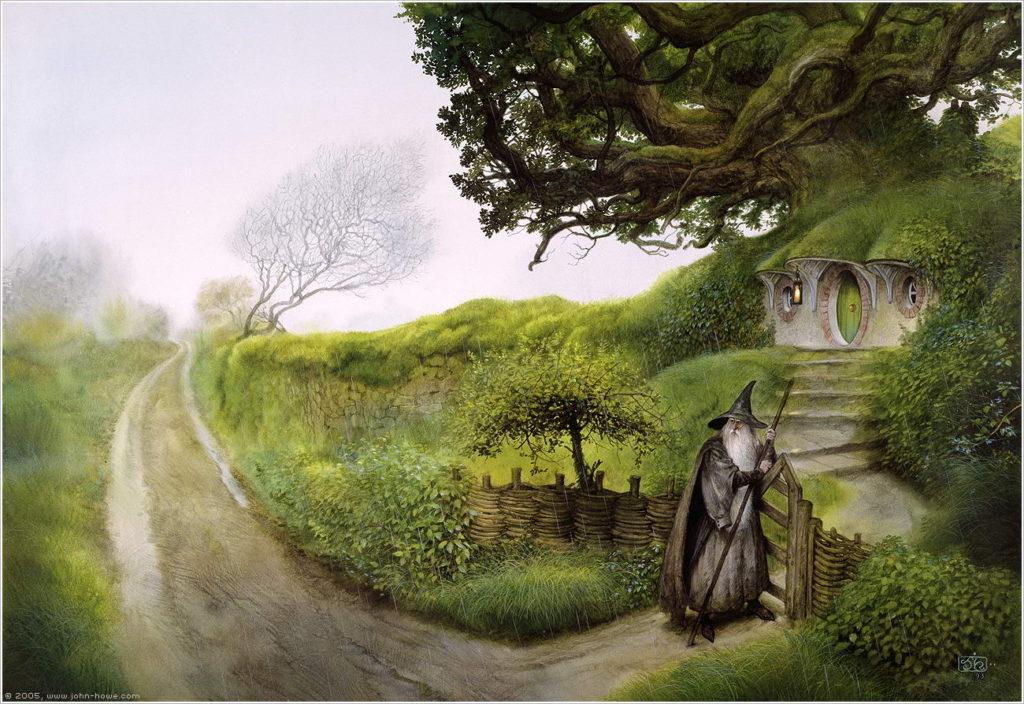

I read the books when I was 12 or so, and enjoyed them, but of course as a 12-year-old would. I re-read them again in my late teens, and began doing illustrations for them in my spare time. (I was buying the Tolkien calendars around then, and illustrating the same themes that were in the calendars). I also did some Lord of the Rings illustrations in art school in Strasbourg. (At the time, in France, Tolkien was almost unknown.) It is only later on, with all the wonderful books published on the writing of Tolkien’s works, that I appreciated their true depth.

This said, I very much see Tolkien as a portal or a threshold to a world of myth and legend – his interests and sources – that is deep, complex and vast. To those worlds, Tolkien is a wonderful introduction.

Let’s start from this reflection: illustrators like you, Ted Nasmith and Alan Lee found themselves having to put their hands on a series of works that are practically born already illustrated by the same author. One might well think that no one can create more heartfelt and effective illustrations than Tolkien himself, the one who conceived the history and world of Middle-earth. So I wonder, with what spirit can an illustrator use to approach this mission?

Tolkien is a master of describing not the appearance of something, but the emotions it provokes in his protagonists. He also adroitly uses his characters to describe places and situations, thus giving us a double layer of meaning and making the description clearer emotionally while preserving the mystery by not over-detailing. For an artist, what is not in a text is as important as what is. While a text should not be contradicted, the undescribed leaves you with a good deal of liberty, which must be taken advantage of. This is where it is possible to bring in personal experience and knowledge.

I think you will find that most illustrators have a fairly thorough, if empirical, grasp of art, history, costume and culture. (I recall how much I enjoyed exchanging on those subjects with Alan Lee). This familiarity is the prerequisite of a large visual vocabulary, which increases the artist’s scope, in the same way that knowing more words in a language allows for more elaborate, more precise and richer writing or speaking.

Tolkien did not create simple drawings to accompany his works, but real masterpieces of graphic art, with precise stylistic elements of reference within the history of art closest to him. In relevance to this, what did you want to keep in your work and what did you deviate from?

I see Tolkien’s artwork as a window into his mind, and a very useful one. They also reinforce the notion that creation is not so neatly divided into writing and painting or drawing, the two skills can contribute by turn to the same universe. I tend to agree with him: his universe is better not illustrated, but painting is my profession, so I will accept the contradiction. This said, while I understand his reluctance, and often talk with readers who would prefer that their imaginations not be “guided” by artwork, I do not think that the text has anything to fear from any picture. If the image does not find a symbiotic relationship with the word, then it is quickly forgotten. If the image persists, then it somehow captures what the text not only says, but more importantly, what it does not say.

Observing your works, not only Tolkien’s ones, we notice how they are pervaded by a sort of Pre-Raphaelite spirit: there are in fact tangible references and citations to a sort of neo-medieval inspired folklore, where popular tradition (trolls, elves) is intertwined with the Arthurian Cycle, the Middle Ages, the legends about the Grail, the Celtic people, etc., etc., characteristics that make their narrative and artistic typology adaptable to the work of the Professor.

But where do these suggestions arise in you? From literature? From childhood stories? From art? Are there any artists from the past who have contributed to your “romantic” formation?

I do not think it would be false to say that modern fantasy is the child of Romanticism and the Victorians, be they Pre-Raphaelite, Symbolist or Decadent. The end-of century grimness and hope, in equal measure, pervade all fantasy from William Morris onward.

Illustrating any literary work is a question of deciding what feels “right”, which is of course a wholly subjective view. When I read a text and find myself with many different options, all of which appeal to me in equal measure, I know I have not yet reached the core of the text itself, or have not appreciated its true value. With Tolkien, I know instinctively what feels “right”, though of course, it can only apply to me and I would not expect anyone to share that view. On the other hand, this feeling of credibility in a fantasy world is crucial. It shows that the extraordinary laws of the fictional universe have been assimilated and that a form of fantastic realism can begin to take shape.

As an example, the mountains that I know the best, the Rockies in North America, for me are no possible to use as reference for Middle-earth. The Alps, when I need visual reference, are just right. On the other hand, for the events of The Silmarillion, I feel that the mountains of Patagonia are better suited.

Of course, there is no logical defence of this. Nonetheless, I can imagine the reasons for it, which come from personal and shared experience and literary resonance. Tolkien was grandly inspired by his walking tour of the Alps, where he walked is a region I know well – I can almost see it from home. Something in his writing, in his descriptions of the Misty Mountains, contains the latent memory of that experience, which in turn resonates with me when I see the mountains themselves. On the other hand, the mountains described in the Silmarillion are grander, wilder and more archetypal in nature. This heightened realism corresponds to my daydreams of visiting Patagonia and seeing those mountain ranges for real. As you can see, inspiration is a mixture of experience, reading and wishful thinking.

Nothing concerning inspiration is straightforward or simple. I regret the tendency to oversimplify an author’s sources of inspiration; scholars seem determined to plant a pin in a map for literally everything Tolkien describes. He did not write a travel book, and wishing to over-clarify his sources is, in my thoughts, an error.

Speaking of romanticism, we note in your illustrations the recurrence of landscapes and settings that really recall the Romantic currents, in particular the German one, both in terms of composition and concept (an element also present in Tolkien’s illustrations). In fact, we often find very impressive natural or artificial scenographies, often in conjunction with natural phenomena of considerable importance, in which man, if present, is relegated to the background, or appears in any case overwhelmed. Is this a correct perception? Are there actually references to German Romanticism? To a particular artist, perhaps Friedrich?

The Romantics were the last painters to try to establish the human being in relation to the landscape, to depict the sense of wonder of the small beings that we are in front of the vastness of nature. (Subsequent painters of nature have removed man altogether, as if, through our destruction of nature, we have demerited and no longer deserve a place.) I feel Romanticism has a role to play in modern times, as a vehicle to promote ecology. The focus and the problems have changed, but the need to address them artistically remains. Our connection to Nature must be redefined.

On the nature of inspiration and inspiration from nature: HORIZONS NEAR AND FAR

On the process of making art: WE ARE THE RAVEN-FED

Observing the various peoples of Middle-earth, both in the film transposition and in the illustrations, what we notice is that to represent the elven “world”, both in the places and in the equipment, you have deviated from the more Nordic style / Celtic in favor of fluid and much more modern lines, which surprisingly recall Art Nouveau. Is there a particular reason for this? Or perhaps purely a stylistic choice?

The images we instinctively conjure up are syncretic and have been forming in humanity’s imagination for a long, long time. Everyone knows what a dragon is like, but they have never seen one, nor have they ever existed.1 Nonetheless, people can happily describe them to you in a good deal of detail. This is shared or common culture, upon which Tolkien draws heavily. The ancestry of the creatures and beings and cultures of Middle-earth is traceable and clear. Seen from that point of view, it makes no sense to take a different approach simply by opposition. Remaining faithful to such a text is to draw what people expect, but to surprise them with creativity and originality.

Here again, we come back to the conviction of what is “right.” I have often had fans tell me very firmly that something I have painted is wrong. “Gollum doesn’t look like that.” I then ask if they can tell me what he does look like. Generally, the reply is: “I’m not sure, but not like that.”

I really enjoy those exchanges, and admire the passion that many readers bring to their appreciation of the stories. On the other hand, none of us are “right.” All the artist can do, bound as he or she is by the need to portray a convincing universe, is make a proposal, a proposition.

It is crucial to leave space for the viewer, to allow them to enter into the image as they enter into a text. I am often told my work is very detailed, but if you look closer, you will see that there is not a great deal of detail, it is simply in the places where it is most useful: to invite the viewer in, to guide them to those less detailed parts of the image where they can each bring their contribution and complete the picture.

Speaking of the adopted illustration technique, it is correct to say that you go from very dynamic and effective sketches to graphite and colour plates in which, however, the sense of “handmade” is totally lost in favour of an exclusive use of digital?

How do you think technology has changed the illustration? To what extent can this technology shape the term “handcrafted illustration” into “digital illustration”?

Tools always shape the hand. The more sophisticated the tool, the more the product of that tool will be influenced by it, regardless of the different hands that use it. This said, traditional and digital illustration are largely the same thing. Each has advantages and disadvantages, qualities and faults.

Changes can be felt in her Magic the Gathering art. For Tolkien, you create open spaces with a strong emphasis on nature and climate, on how the plan’s landscape differs from Lórien to Shire and Mordor. Does this change come from Tolkien’s text and environmental concerns or the need to portray a game mechanic?

I have never done very much artwork for Magic the Gathering – only two pieces. They are not really different from the rest of my work.

I imagine you are thinking of the other John Howe (yes, same name, different person), who has done many Magic cards. We were in touch some time ago, and agreed to sign each other’s cards for fans, but I suspect I sign a lot more of his than he does of mine. (I do always warn people, and explain that I am an imposter, but they are usually happy to get a signature).

Mr. Howe, in a recent blog post, you hinted at how it is up to the reader to make art meaningful. As children, we can immerse ourselves in Tolkien’s Middle-earth or C.S. Lewis, or in the sky of Neverland with a clean perspective, without the worries of too much fantasy or cohesion in the construction of the world. How did you make art meaningful to yourself over the years? How does your political and social outlook affect your art, if so? For example, by reviewing Tolkien’s work multiple times for different projects – such as calendars, books, Amazon series and all six films – did you try to reach for new sensations? How would you portray the halls of Moria in the Covid-19 era?

I could not imagine doing the same thing the same way twice. Nothing is engraved in stone, the artwork one does today will not be the same way one thinks tomorrow. Falling back on what you “know” too well is an error to be avoided. There is always something new to be explored. The text does not change, but we do: our experience changes us, our knowledge aids us, change is part of our view of the world.

I try not to tie my work to current affairs, that is the domain of the journalist. I think the issues at stake in good fantasy literature and deeper and broader than last week’s, or even the last year’s events, and touch on questions which have accompanied humanity a long time. Naturally, we are all creatures of our time, so modern sensibilities and opinions certainly pervade the fabric of my work, but they are not the goal.

I used to believe that we had the images we do in our heads, that the art of painting consisted of getting them out onto paper or canvas. Now I realise that is not true. What we possess are the techniques, the experience and the desire to create images, but the images are in the world. Painting means reaching out to discover them.

I am often asked about artist’s block, about being confronted with the blank page and having no inspiration. That blank page is not a page. It is a window looking out on a three-dimensional, infinite space, into which you can reach with the tip of your pencil to uncover what is already there. Drawing is a dialogue, an exchange between the theme, the artist and what is appearing on the paper. As in any dialogue, if one participant does all the talking, there is no exchange. Drawing is part way between a meditation and a conversation.

Twenty years have passed since the Tolkien universe was brought to the masses through the film adaptations of Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings. What was the process of creating Middle-earth like? What reference points did you consider to create the architectural styles, armour, weapons, hardware and daily life of the various races of Middle-earth? Looking at the movies today, would you change anything from the original script?

I certainly would not presume to offer my opinion on the script! I am not a writer, and know nothing about the incredibly difficult task of adapting a novel to the screen. Are there things I would like to see included that were left out? Of course! I think we all regret Tom Bombadil is not in the movies, for example. Also, parts of the backstory of various characters would have been lovely, but the movies would have been twice the length!

At one point on The Hobbit, the script took us to the Barrow-Downs, and we visited an extraordinary place on a farm in the North Island, which would have been so wonderfully perfect. It was incredibly exciting, and the scenery was so terrifically strange it would have been hard to believe it was natural. Alas, the scene got written out of the script.

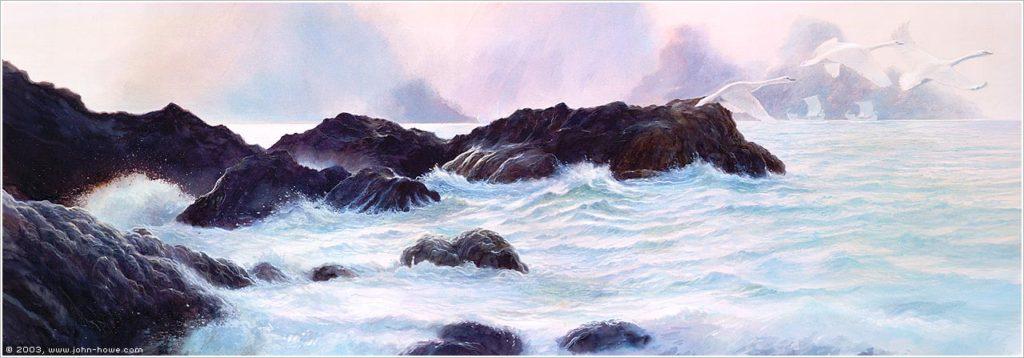

We visited some wonderful places on scouting trips in New Zealand. My one regret is that neither The Lord of the Rings or The Hobbit really take us to the edge of the ocean; New Zealand has some of the most beautiful coastlines on Earth.

For the creation of the visuals of the movies, I would refer you here to my newsletter: JOURNEY INTO WILDERLAND

Looking at the trilogies of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit we immediately notice the different choices in the use of special effects. In The Lord of the Rings we have a huge amount of stuntman, orcs, soldiers, horses, weapons and various materials. Instead, in The Hobbit, we see a great use of special effects from computer graphics. Who manages these choices and what has changed in the style and production of the two trilogies?

Both series used the latest technology that was available when they were made. There is a lot of VFX in LOTR, but you are right, there is more in The Hobbit because the technology evolved.

Is there another non-Eurocentric fantasy you fell in love with and that you would like to work on?

Of course! There are Chinese and Japanese epics I would love to visit through painting, as well as the culture of the Himalayas.

We recently read on your Facebook page about the announce of the statue The Witch-King by U-man Studio, created from your design project. What is it like for you to see your creation come out of paper and become palpable? Could you tell us a little about the process of transforming an illustration into a statue?

I have not seen the final statue yet, but did see a prototype in Shanghai, where it already looked very nice. I am very excited to see the final version. Of course, one of the challenges is that things do not always work from every side, since you only draw them from one. I did a number of sketches to help the sculptors.

The statue was a limited edition of 300 copies. They went on line for pre-order and sold out in one second. We are discussing the choice of subject for the next one. Is there a picture you would like to see as a statue?

Following the announcement of The Tolkien Calendar 2021 and the illustrated edition from you, Ted Nasmith and Alan Lee’s book Unfinished Tales of J.R.R. Tolkien, what will we see new in these volumes? How is it for you to still work with the great Tolkien illustrators of the present day?

I have not seen the others’ work yet. I am looking forward to seeing what they did. I believe the book will be published in October.

What advice can you give to new emerging artists?

Be sincere. I know that sounds a little trite, but by sincerity, I mean treating both the subject matter and the client with respect. Be original. This means improving and constantly augmenting your visual “vocabulary”.

Do you want to send a message to our Italian Tolkienists friends and to your fans who read us?

Simply thank you. Without the fans and enthusiasts and their energy and dedication, my profession would not exist.

Notes:

1 Concerning Tolkien’s dragons: A FEW WORDS ABOUT DRAGONS