di Benedetto Ardini

L’ANELLO DI SILVIANUS E L’ANELLO DI SAURON

VERA INFLUENZA O MERA SPECULAZIONE?

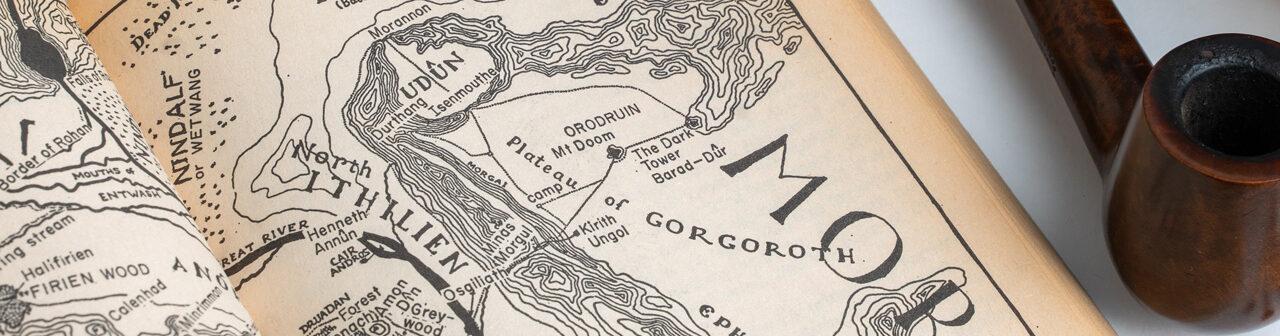

In questo articolo ci poniamo l’obiettivo di analizzare, discutere e fare chiarezza su una teoria secondo la quale l’anello di Silvianus (chiamato anche anello di Vyne), oggetto rinvenuto nel 17861 nei pressi di Silchester in Inghilterra e databile al IV secolo d.C.2, possa ‘aver ispirato a Tolkien l’idea dell’Unico Anello, oggetto centrale dei romanzi Lo Hobbit e Il Signore degli Anelli’3. L’anello di Silvianus ha la particolarità di essere fatto d’oro e di recare le scritte in latino SENICIANE VIVAS IIN DE (Seniciano vive in dio); inoltre all’inizio del XIX secolo, nel sito di un tempio romano nei pressi di Lydney (nel Gloucestershire), è stata rinvenuta una lamina di piombo incisa a graffio recante una maledizione, sempre in latino, inerente l’anello di Vyne e la cui traduzione è:

«Per il dio Nodens. Silvianus ha perso un anello e ne ha donato una metà [del suo valore] a Nodens. Tra tutti quelli chiamati Senicianus non sia concessa buona salute fino a che esso non sia riportato al tempio di Nodens»4

Dall’iscrizione è quindi possibile supporre che l’anello fosse stato rubato da un tale Senicianus a cui Silvianus, il proprietario originario, mandava questa maledizione.

Riproduzione dell’iscrizione sulla lamina pubblicata nel report degli scavi archeologici di Lydney5

Il collegamento di tutto ciò con J.R.R. Tolkien si ebbe quando l’archeologo Mortimer Wheeler si consultò con il Professore a riguardo del nome del dio invocato nella maledizione (e presente in altri due piatti di bronzo rinvenuti nello scavo di Lydney6): nome su cui lo stesso Tolkien scrisse il saggio intitolato The Name ‘Nodens’ tra il 1929 e il 19307. In questo scritto Tolkien afferma che Nodens (forma latinizzata di un possibile nominativo celtico noudons8 che possibilmente significava “cacciatore”9) era molto probabilmente una divinità adorata dalla popolazione gaelica irlandese10 (e introdotta successivamente anche nell’ovest della Britannia in cui il suo culto continuò anche ben dopo l’arrivo del Cristianesimo11): infatti è collegabile alla figura di Núadu12, il re dei Túatha dé Danann che erano gli antichi possessori dell’Irlanda e considerati come forme ridotte di antichi dei13.

Considerando il lavoro di Tolkien su The Name ‘Nodens’, è fuori discussione che il Professore ebbe un contatto diretto con la storia dell’anello di Silvianus.

A questo punto, contestualizzato l’anello di Silvianus e il legame con Tolkien, cerchiamo di rispondere alla domanda se tale esperienza abbia avuto veramente un impatto potenzialmente centrale nello sviluppo narrativo dell’Anello di Sauron.

Elementi come l’oro e le scritte incise sull’anello di Vyne potrebbero richiamare le caratteristiche fisiche originarie dell’Unico Anello descritte nel legendarium tolkieniano14 inoltre, come fa notare la studiosa Helen Armstrong15, anche lo stesso sito archeologico di Lydney è collegabile con la storia degli Anelli del Potere della Seconda Era: infatti l’attributo Argat-lam, Mano d’Argento, associato al dio Nodens16 e il territorio circostante a Lydney (dove è presente uno sperone chiamato Colle del Nano17) possono aver ispirato il personaggio di Celebrimbor (celebrin, “argento” + paur, “pungo”18) e dei reami di Eregion e Moria19.

In aggiunta a tutti questi aspetti, la maledizione di Silvianus a Senicianus potrebbe benissimo essere associata a quella di Gollum a Bilbo Baggins nel libro The Hobbit:

“Maledetto il Baggins! È scomparso! Cos’ha in tasssca? Oh sì che indoviniamo, tesssoro. L’ha trovato, sì l’ha trovato […] È così. Maledetto! Ci è scivolato via, dopo tutti questi anni e anni! È scomparso, gollum.”20

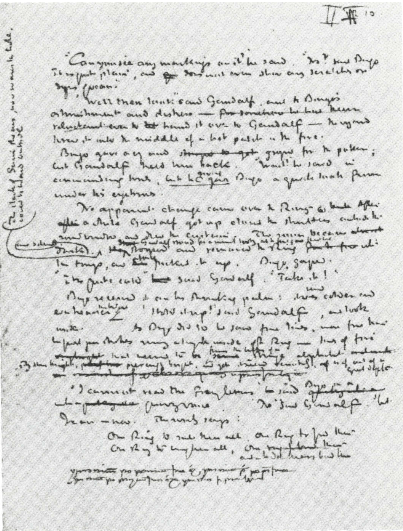

Il fatto che Tolkien stesse scrivendo la storia di The Hobbit proprio negli anni dello scavo di Lydney21 potrebbe sembrare un forte argomento a favore della tesi di un’influenza diretta dell’anello di Silvianus su quello trovato da Bilbo Baggins, poi rivelatosi l’Unico. Tuttavia una simile considerazione, facente leva sulla vicinanza temporale degli eventi, non è assolutamente supportabile sulla base del processo creativo del libro. Infatti nella prima edizione di The Hobbit, pubblicata nel settembre 1937, né le caratteristiche fisiche dell’Anello di Sauron (oro con iscrizioni), né la maledizione di Gollum, né tanto meno il collegamento con Sauron, l’Eregion e gli Anelli del Potere erano presenti22: l’anello trovato da Bilbo era un semplice anello magico con nessun legame con la più complessa trama definitiva che sarebbe stata sviluppata da Tolkien solo tra il 1938 e il 1941 durante la scrittura del sequel The Lord of the Rings23.

Pagine del manoscritto di The Lord of the Rings conservato alla Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA. A sinistra: descrizione delle scritte dell’Anello; a destra: i versi degli Anelli e l’introduzione del concetto di Anello Dominante (Unico Anello) nella narrativa24.

Quindi è fuori discussione che l’Anello di Sauron sia stato sviluppato nella narrativa della Terra di Mezzo almeno 8 anni dopo il lavoro di Tolkien riguardante l’Anello di Silvianus. Comunque, potrebbe essere che, dopo questi anni, il Professore abbia ripescato il ricordo di tale anello e lo abbia utilizzato per progredire con la storia del suo libro: ma, allora, se analizziamo le possibili fonti che potrebbero aver inconsciamente ispirato Tolkien, potremmo stilare una lista di tanti altri anelli che, al pari (se non di più) di quello di Silvianus, potrebbero aver influenzato l’Unico. Per esempio, come notato da John Rateliff, c’è l’anello presente nell’Orlando Furioso di Ariosto che, esattamente come quello di The Hobbit, si rivela uno strumento utile al portatore per evitare danni e superare sfide altrimenti insormontabili25 (l’anello permette alla femme fatale Angelica di diventare invisibile assieme al suo cavallo26). Altri tre anelli dell’invisibilità sono stati individuati da Douglas Anderson: l’anello di Gige nel secondo libro della Repubblica di Platone, e quelli presenti nei racconti raccolti da Andrew Lang come The Enchanted Ring in The Green Fairy Book e The Dragon of the North in The Yellow Fairy Book27: tutte fonti che Tolkien senz’altro o conosceva o comunque potrebbe aver letto28. Sempre di Andrew Lang c’è anche la storia The Magic Ring dove un anello magico conferisce un grande potere al protagonista permettendogli di far comparire 12 giovani uomini (con poteri sovrannaturali) al suo servizio29: da notare anche che The Magic Ring venne originariamente scelto da Tolkien come titolo del sequel di The Hobbit, solo successivamente cambiato in The Lord of the Rings30. Tra le fonti di ispirazione potremmo includere anche l’anello dei Nibelunghi31 anche se lo stesso Tolkien ha affermato che non c’è alcuna somiglianza fra tale anello e quello di Sauron32.

Dopo questa carrellata di anelli, tutti potenzialmente ottimi spunti per The Lord of the Rings, quella che poteva sembrare un’influenza sicura da parte dell’anello di Silvianus in realtà non può che essere messa in secondo piano: il bagaglio culturale di Tolkien era talmente vasto e complesso che porre equazioni e corrispondenze biunivoche tra elementi del suo legendarium e specifici riferimenti storico-letterari è una forzatura. Per l’appunto gli studiosi Wayne Hammond e Christina Scull nel loro Tolkien Companion and Guide, ormai una pietra miliare degli studi tolkienieni, negano una reale influenza degli scavi archeologici di Lydney con lo sviluppo di The Hobbit e The Lord of the Rings33 e lo studioso Tom Shippey tende a vedere in questa faccenda più un’influenza generale nelle modalità del processo creativo (mostrate da Tolkien nel saggio The Name ‘Nodens’) che si ripercuotono nello sviluppo del legendarium34 piuttosto che una banale somiglianza tra anelli.

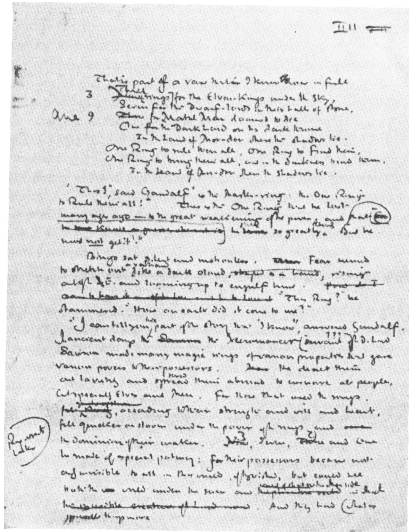

Nell’Unico Anello è racchiuso il concetto filosofico che lo stesso Tolkien chiama ‘Macchina’, che è lo strumento con cui Sauron, ribellatosi al Disegno Divino e desiderando una sua propria creazione (una Terra di Mezzo bella come Valinor, il Reame Beato, e indipendente35), vuole piegare a sé la realtà e gli altri36. Nell’Anello di Sauron c’è il Potere che permette di bastare a sé stessi e di far andare il corso degli eventi secondo il proprio desiderio: quindi qualcosa da cui, in fondo, quasi tutti sono tentati. Per tale motivo l’Unico non è un semplice gioiello dalla natura misteriosa (o sovrannaturale) ma è puro strumento del Male37 nella sua forma peggiore che fa leva proprio sulla drammaticità e caducità della vita38. Le soluzioni che pone sono facili ma con conseguenze nefaste:

“No!” gridò Gandalf, balzando in piedi. “Con quel potere il mio sarebbe troppo grande e terribile. E su di me l’Anello acquisterebbe un potere ancor più grande e micidiale […] L’Anello tocca il mio cuore con la pietà, pietà per la debolezza, e il desiderio di avere la forza per compiere il bene. Non mi tentare! Non oso prenderlo, neanche per custodirlo, inutilizzato. Troppo grande sarebbe la voglia di avvalermene per le mie forze. Ne avrei tanto bisogno.”39

“Al posto dell’Oscuro Signore vorresti mettere un Regina” […] Poi lasciò ricadere la mano e la luce svanì, e all’improvviso rise di nuovo ed ecco! era rimpicciolita: un’esile donna elfica […] “Ho superato la prova,” disse. “Mi sminuirò, andrò all’Ovest e rimarrò Galadriel.”40

I momenti di prova di Gandalf e Galadriel contro la tentazione dell’Anello nel film The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring di Peter Jackson.

A detta del suo stesso autore, il tema principale di The Lord of the Rings è infatti proprio la morte/mortalità e il desiderio di immortalità di ciascuno41: aspetti in cui l’Anello si pone come risolutore ma che finisce solo rispettivamente per amplificare42 e contraffare43. Infatti la vera immortalità e pienezza dell’essere non sono di questo mondo, della Terra di Mezzo: tutto quello che ci viene donato sono rapide visioni di una vera felicità oltre l’inesorabile e lunga sconfitta di questa vita44.

L’Unico Anello di The Lord of the Rings è quindi ben altro di un semplice espediente narrativo, tratto da un oggetto con delle scritte, ma porta in sé riflessioni profonde dell’autore sulla vita e sulla morte e sul “farsi da sé” oppure “seguire un disegno” con la fiducia in un Bene più grande oltre il Mondo: al lettore la libertà di rendere propri questi messaggi.

- “[…] gold ring lost by the Roman Silvianus at the temple of Nodens at Lydney in the late fourth century, found 100 miles away in 1786, and now at The Vyne near Basingstoke, Hampshire.” (Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina; Tolkien Companion and Guide: Volume 3: Reader’s Guide PART 2 . Edizione 2017, The Name ‘Nodens’, pag.826).

- Si veda https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/apr/02/hobbit-tolkien-ring-exhibition

- Si veda https://it.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anello_di_Silvianus

- Questo testo è riportato nella forma originaria nel report dello scavo archeologico di Lydney: “Devo Nodenti. Silvianus anilum perdedit ; demediam partem donavit Nodenti. Inter quibus nomen Seniciani, nollis petmittas sanitatem donec perfera(t) usque templum [No]dentis” e tradotto in “To the god Nodens. Silvianus has lost a ring; he hereby gives half of it (i.e. half of its value) to Nodens. Among those who are called Senicianius, do not allow health until he brings it to the temple of Nodens” (Wheeler, R.E.M. and T.Y. Wheeler. “Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.” Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1932): 1-137.)

- Si veda Fig.28 in (Wheeler, R.E.M. and T.Y. Wheeler. “Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.” Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1932), pag.100.).

- “This name occurs in three inscriptions : C.J.L. vii, 138 d( eo) M( arti ?) Nodonti, C.I.L: vii, 139 deo Nudente, C.I.L. vii, 140 devo Nodenti .. .donavit Nodenti .. . temp/um [No]dentis.” (Wheeler, R.E.M. and T.Y. Wheeler. “Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.” Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1932), Appendix I, pag.132.). Si vedano pag.100-101 della stessa fonte per le iscrizioni complete (e rispettive traduzioni) e descrizioni dei piatti di bronzo.

- Il saggio The Name ‘Nodens’ fu pubblicato nel 1932 come Appendice I al Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman, and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire (scaricabile al link https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/50813) e poi ripubblicato nel 2007 nel volume 4 di Tolkien Studies. “Note, first published as Appendix I, pp. 132–7, in the Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman, and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire by R.E.M. Wheeler and T.V. Wheeler (Oxford: Printed at the University Press by John Johnson for The Society of Antiquaries, 1932). […] Tolkien researched Nodens and wrote a note on the subject probably in 1929 or 1930, at the request of R.E.M. (later Sir Mortimer) Wheeler, Keeper and Secretary of the London Museum. Wheeler had the finished note in hand apparently well before 2 December 1931, when he informed Tolkien that a report on the Lydney Park excavations was to be issued by the Society of Antiquaries, including Tolkien’s note […] The Name ‘Nodens’ was reprinted in Tolkien Studies 4 (2007), pp. 177–83.” (Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina; Tolkien Companion and Guide: Volume 3: Reader’s Guide PART 2 . Edizione 2017, The Name ‘Nodens’, pag.826).

- “Native Keltic words had no ō. […] This sound [ou] in British approaches ō, and was equated with Latin ō in the British pronunciation of Latin and vice versa; so that o would be a natural early choice of the symbol […] The inscriptions most probab1y represent, therefore, a Keltic stem *noudont- (*noudent- ?), provided with Latin case-endings. Now *noudont- (nom. *noudons>noudos>noudus, gen. noudontos, dat. noudonti or noudontai)” (Wheeler, R.E.M. and T.Y. Wheeler. “Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.” Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1932), Appendix I, pag.132-133.).

- “In Gothic, the earliest recorded of the Germanic group and preserved in a form spoken at a time when Nodens’ temple possibly still had votaries, clear traces remain of an older sense. There ga-niutan means ‘ to catch, entrap (as a hunter)’” (Wheeler, R.E.M. and T.Y. Wheeler. “Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.” Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1932), Appendix I, pag.136.).

- “But the fact that outside Ireland (where the name figures largely) Nodons-Nuada occurs only in Britain, in the west, in one place, and nowhere else in the Keltic area, never in Gaul, has led to the more likely conjecture that Nodens is a Goidelic god, 1 probably introduced eastward into Britain, unless one can believe that the Goidels reached Ireland by way of Britain and left his cult behind them.” (Wheeler, R.E.M. and T.Y. Wheeler. “Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.” Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1932), Appendix I, pag.133.).

- “In 1928 excavations on a site near Lydney in the west of England had revealed a temple devoted to some kind of mystery cult and still flourishing in the fourth century, i.e. well after the introduction of Christianity to England. The temple was eventually abandoned as a result of the barbarian and also non-Christian English, who however had their own cults.” (Tom Shippey, The Road to Middle-earth: How J.R.R. Tolkien created a new mithology, ch. 2 Philological Inquiries, pag. 40, Kindle Edition)

- “The authorities (Rhŷs, Whitley Stokes, and Tolkien) all agree that Nodens is phonetically equivalent to the Irish Nuada” (Wheeler, R.E.M. and T.Y. Wheeler. “Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.” Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1932), pag.39).

- “Nuadu (Argat-lam ‘of the Silver Hand’) was the king of the Tuatha de Danann, the possessors of Ireland before the Milesians. The Tuatha de Danann may with some probability, amid the wild welter of medieval Irish legend, be regarded as in great measure the reduced form of ancient gods and goddesses.” (Wheeler, R.E.M. and T.Y. Wheeler. “Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.” Reports of the Research Committee of the Socieîv of Antiquaries of London9 (1932), Appendix I, pag.133.).

- Si prendano per esempio le parole della pergamena di Isildur: “Already the writing upon it, which at first was as clear as red flame, fadeth and is now only barely to be read. It is fashioned in an elven-script of Eregion […] The Ring misseth, maybe, the heat of Sauron’s hand, which was black and yet burned like fire, and so Gil-galad was destroyed; and maybe were the gold made hot again, the writing would be refreshed.” (J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch.2 The Council of Elrond, pag.252, Ebook Edition © August 2022 ISBN: 9780007322596).

- “Helen Armstrong, after visiting the site, suggests that exposure to this project may have been a source of inspiration for Celebrimbor and the fallen realms of Moria and Eregion (Armstrong, 13). She mentions the names of Silver-Hand and Dwarf’s Hill, as well as small axes found inside the mine’s trapdoor […]” (Michael D.C. Drought, J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, pag.1666-1667, Taylor and Francis. Ebook edition, ISBN–10: 0-415-96942-5)

- Si veda nota 13.

- “At one time it seems that the spur was known popularly by the name of the Dwarf’s Hill.” (Wheeler, R.E.M. and T.Y. Wheeler. “Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.” Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1932), Prefatory Note, pag.1).

- “Celebrimbor means ‘silver-fist’, from the adjective celebrin ‘silver’ (meaning not ‘made of silver’ but ‘like silver, in hue or worth’) and paur (Quenya quárë) ‘fist’ […]” (The Silmarillion, Appendix: Elements in Quenya and Sindarin Names, Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2011 ISBN: 9780007322565)

- Si veda la collaborazione dei Nani di Moria con gli Elfi di Eregion e la collaborazione tra Elfi e Sauron nella creazione degli Anelli del Potere: “Eregion was nigh to the great mansions of the Dwarves that were named Khazad-dûm, but by the Elves Hadhodrond, and afterwards Moria. […] It was in Eregion that the counsels of Sauron were most gladly received […] they hearkened to Sauron, and they learned of him many things, for his knowledge was great […] they made Rings of Power. […] Now the Elves made many rings; but secretly Sauron made One Ring to rule all the others […]” (The Silmarillion, Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age, pag.307, Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2011 ISBN: 9780007322565) Si vedano le descrizioni dei luoghi nel Signore degli Anelli: “The only road of old to Moria from the west had lain along the course of a stream, the Sirannon, that ran out from the feet of the cliffs near where the doors had stood. […] There used to be a shallow valley beyond the falls right up to the Walls of Moria, and the Sirannon flowed through it with the road beside it.” (J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch.4 A Journey in the Dark, pag.300-301, Ebook Edition © August 2022 ISBN: 9780007322596) che richiamano alcuni aspetti del sito vicino Lydney come la presenza del fiume e delle valli tra i monti : “Between the mouth of the Wye and Newnham-on-Severn, the Forest of Dean thrusts southwards towards the Severn along a series of irregular ridges and spurs, divided here and there by small streams. […] The spur is flanked by deep glens […]” (Wheeler, R.E.M. and T.Y. Wheeler. “Report on the Excavation of the Prehistoric, Roman and Post-Roman Site in Lydney Park, Gloucestershire.” Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London (1932), Prefatory Note, pag.1).

- (J.R.R. Tolkien, Lo Hobbit, cap.V Indovinelli nell’oscurità, pag.100, Prima edizione digitale: ottobre 2018). In lingua originale è: “Curse the Baggins! It’s gone! What has it got in its pocketses? Oh we guess, we guess, my precious. He’s found it, yes he must have. […] That’s it. Curse it! It slipped from us, after all these ages and ages! It’s gone, gollum.” (J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit, cap.V Riddles in the Dark, pag.84, Ebook edition).

- La scrittura dei primi 12 capitoli e del XIV di The Hobbit avvenne tra il 1928 e il 1933 (il saggio The Name ‘Nodens’ è databile tra il 1929 e il 1930, come abbiamo visto prima): «Tolkien chiaramente ebbe l’ispirazione per la prima frase [il famoso incipit di The Hobbit] mentre d’estate ordinava i compiti degli studenti, e ciò sembra avvenuto probabilmente nei tre anni tra il 1928 e il 1930 […] Sicuramente attorno al gennaio 1933 dovette raggiungere la fase C nella preparazione del dattiloscritto, in tempo perché C.S. Lewis leggesse il testo» – Tolkien, J. (2014). Lo Hobbit Annotato (V edizione Tascabili Bompiani gennaio 2014 ed.). Bompiani, ‘Introduzione’, pag.21

- Nella prima edizione di The Hobbit ci sono più di quaranta riferimenti all’anello e nessuno di essi ne indica nello specifico il materiale e fattezze (si legga o una prima edizione di The Hobbit oppure (Tolkien, J.R.R. The Hobbit Facsimile First Edition 2016 ed.)) se non che è di metallo (non specificato il tipo) ed è piccolo («a tiny ring of cold metal»). I riferimenti al fatto che l’anello è d’oro («He [Gollum] had a ring, a golden ring, a precious ring» (J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit, cap.V Riddles in the Dark, pag.80, Ebook edition)) e al fatto che Gollum sia furioso di aver perso il suo anello sono elementi introdotti solo a partire dall’edizione di The Hobbit del 1951: per i dettagli si veda la discussione alla nota 25 a pag.143 di (J.R.R.Tolkien, Lo Hobbit Annotato (V edizione Tascabili Bompiani gennaio 2014 ed.). Bompiani).

- I primi tentativi di sviluppo della storia dell’Anello nel sequel di The Hobbit risalgono al 1938 quando Tolkien scrive la nota “Make return of ring a motive” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.6, The Return of the Shadow, The First Phase, ch. I A Long Expected Party, (v) ‘The Tale that is Brewing’, pag.58, Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2019 ISBN: 9780007348237). Wayne Hammond e Christina Scull sottolineano che nel febbraio 1938 Tolkien stava considerando come la storia si sarebbe dovuta sviluppare: “1 February 1938 […] Tolkien seems not to have proceeded beyond the several versions of the first chapter of The Lord of the Rings, but is considering how that story might develop.” (Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina; Tolkien Companion and Guide: Volume 1: Chronology . Edizione 2017, pag.226). Il fatto che l’Anello sia d’oro e che abbia delle scritte (visibili quando viene messo a contatto con una sorgente di grande calore) è una caratteristica che, molto probabilmente, Tolkien delinea non prima della fine del 1938 nel capitolo Ancient History (appartenente alla seconda e terza fase di scrittura di The Lord of the Rings delineata da Christopher Tolkien), il precursore del definitivo capitolo 2 The Shadow of the Past di The Lord of the Rings. Per la datazione dell’inizio dell’inizio della terza fase si veda: “[…] in October 1938 the third phase had not been begun, or had not proceeded far […] while when my father wrote of having had to set the work aside in December 1938 it was to the third phase that he was referring […]” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.6, The Return of the Shadow, The Third Phase, ch. XIX The Third Phase (1): The Journey to Bree, pag.378, Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2019 ISBN: 9780007348237). Per i riferimenti all’Anello in Ancient History si veda: “It looked to be made of pure and solid gold, thick, flattened, and unjointed. […] he saw fine lines, more fine than the finest pen strokes, running along the inside of the Ring – lines of fire that seemed to form the letters of a strange alphabet.” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.6, The Return of the Shadow, The Third Phase, ch. XIX The Third Phase (1): The Journey to Bree, Chapter II: ‘Ancient History’, pag.313-314, Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2019 ISBN: 9780007348237). Per quanto riguarda il 1941 come probabile anno in cui si ha la concezione definitiva del rapporto tra Sauron e gli Elfi nella creazione degli Anelli del Potere si veda l’articolo al link https://tolkienitalia.net/la-storia-di-galadriel-parte-1/ .

- Si veda (The History of Middle-earth, vol.6, The Return of the Shadow, The Second Phase, ch. XV Ancient History, pag.314-318, Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2019 ISBN: 9780007348237).

- «With Angelica’s ring, we see a theme that would become common among enchanted rings: a duplication (sometimes a multiplicity) of arbitrarily selected powers, making them devices able to protect the wearer from any harm and granting him whatever powers the dictates of the plot require» – Rateliff, J. D. (2007). The History of The Hobbit (Kindle 2011 ed.). HarperCollins, Chapter V ‘Gollum’, section ‘iii.The Ring’

- «Angelica’s ring has the power not just of rendering her invisible, but her mount as well so long as she is touching it» – Rateliff, J. D. (2007). The History of The Hobbit (Kindle 2011 ed.). HarperCollins, Chapter V ‘Gollum’, section ‘iii.The Ring’

- «Gli anelli dell’invisibilità li possiamo ritrovare nella storia di Gige nel secondo libro della Repubblica di Platone (c. 429-347 a.C.). La storia è poco più di un aneddoto, in cui l’anello d’oro rende invisibili quando il castone è girato verso l’interno della mano, e si trona visibili se lo si gira all’esterno. I talismani dell’invisibilità sono molto comuni nelle storie immaginarie, e gli anelli che attribuiscono l’invisibilità si ritrovano in due storie nelle raccolte curate da Andrew Lang: “The Enchanted Ring” in The Green Fairy Book (1892) e “The Dragon of the North” in The Yellow Fairy Book (1894)» – Tolkien, J. (2014). Lo Hobbit Annotato (V edizione Tascabili Bompiani gennaio 2014 ed.). Bompiani, capitolo 5 ‘Indovinelli nell’oscurità’, nota 31 a pag.149-150

- Tolkien possedeva i libri di Andrew Lang, in particolare il Green Fairy Book e il Yellow Fairy Book: “1266.______. The Green Fairy Book. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1892.” “1285. ______. The Yellow Fairy Book. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1894.” (Cilli, Tolkien’s Library, Tolkien’s Library, pag.471 and pag.477, ISBN-13: 978-1-911143-68-0). Sul fatto che Tolkien con buona probabilità conoscesse Ariosto si può dedurre da una lettera: “I am pleased to find that the preliminary opinions are so good, though I feel that comparisons with Spenser, Malory, and Ariosto (not to mention super Science Fiction) are too much for my vanity!” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°145). A riguardo di Platone è ragionevole che Tolkien fosse a conoscenza del Repubblica infatti, come fa notare Humphrey Carpenter, la letteratura greca era un interesse condiviso da lui e gli altri suoi amici del T.C.B.S.: “Yet common to these three enthusiastic schoolboys was a thorough knowledge of Latin and Greek literature […]” (Humphrey Carpenter, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography, ch.IV ‘T.C.,B.S., ETC.’ pag.70, Ebook Edition © MAY 2011 ISBN: 9780007381258) e Tolkien la studio nella prima parte del suo percorso universitario: “Michaelmas Term 1911 Tolkien begins to read Literae Humaniores or Classics, mainly Greek and Latin authors but also Philosophy and Classical History.” (Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina; Tolkien Companion and Guide: Volume 1: Chronology . Edizione 2017, pag.34)

- “[…] in that ring lies a magic power; you have only to throw it from one hand to the other, and at once twelve young men will appear, who will do your bidding, no matter how difficult, in a single night.’ […] Martin threw his ring from the palm of one hand into the other, upon which twelve youths instantly appeared, and demanded what he wanted them to do.” (Andrew Lang, The Yellow Fairy Book, The Magic Ring, pag.108, Ebook Edition)

- Si veda il catalogo alla mostra Tolkien Maker of Middle-earth (dov’è riportata anche una foto della pagina di copertina del manoscritto originario di The Lord of the Rings): “Its [sequel of The Hobbit’s] unexpected growth is clearly illustrated by this early title page, on which ‘The Magic Ring’ has been replaced by ‘The Lord of the Rings’” (Catherine McIlwane, Tolkien Maker of Middle-earth, pag.330-331, ISBN:9781851244850 (hardback))

- Tolkien lavorò ad un poema sulla saga dei Volsunghi in un periodo poco successivo al saggio The Name ‘Nodens’: si tratta di Völsungakviða en nýja dove è presente l’anello maledetto dal nano Andvari: “Loki is sent to find this, and having caught the dwarf Andvari in the form of a pike, demands his hoard, even the ring on his hand, as the price of freedom. Andvari curses the ring: it will bring death to two brothers and seven princes, and bring an untimely end to Ódin’s hope.” (Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina; Tolkien Companion and Guide: Volume 3: Reader’s Guide PART 1 . Edizione 2017, The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún, Völsungakviða en nýja: Synopsis, pag.669-670). “?Late 1931–?1932 […] Around this time Tolkien also writes two companion poems, Völsungakviða en nýja (‘The New Lay of the Völsungs’) and Guðrúnarkviða en nýja (‘The New Lay of Gudrún’) […]” (Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina; Tolkien Companion and Guide: Volume 1: Chronology . Edizione 2017, pag.170)

- “The Ring is in a certain way ‘der Nibelungen Ring’. . . . Both rings were round, and there the resemblance ceases.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°229).

- “Nor is there any reason to believe, despite much wishful thinking, that Tolkien was influenced in writing The Hobbit by the folk-connection between Lydney and dwarves, hobgoblins, and little people, or – at an even further stretch – that he took the idea of the ring in The Hobbit (later the One Ring in The Lord of the Rings) from a gold ring lost by the Roman Silvianus at the temple of Nodens at Lydney” (Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina; Tolkien Companion and Guide: Volume 3: Reader’s Guide PART 2 . Edizione 2017, The Name ‘Nodens’, pag.826).

- “More generally, Shippey describes Tolkien’s essay as a clear example of “the interaction of poetry with philology” that helped thicken the “brew that was to become his fiction” (Shippey, 32). He discusses the influence it may have had in shaping Tolkien’s ideas regarding the nature of stories over time, valuing most in literature the “hints at something deeper further on” (Shippey, 49).” (Michael D.C. Drought, J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, pag.1666-1667, Taylor and Francis. Ebook edition, ISBN–10: 0-415-96942-5)

- Si vedano per esempio le parole di Sauron agli elfi di Eregion: “But wherefore should Middle-earth remain for ever desolate and dark, whereas the Elves could make it as fair as Eressëa, nay even as Valinor?” (The Silmarillion, Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age, pag.307, Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2011 ISBN: 9780007322565) Si vedano anche le parole di Tolkien: “He [Sauron] had gone the way of all tyrants: beginning well, at least on the level that while desiring to order all things according to his own wisdom he still at first considered the (economic) well-being of other inhabitants of the Earth.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°183)

- “[…] the sub-creator wishes to be the Lord and God of his private creation. He will rebel against the laws of the Creator – especially against mortality. Both of these (alone or together) will lead to the desire for Power, for making the will more quickly effective, – and so to the Machine (or Magic). By the last I intend all use of external plans or devices (apparatus) instead of development of the inherent inner powers or talents – or even the use of these talents with the corrupted motive of dominating: bulldozing the real world, or coercing other wills.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°131)

- In una lettera Tolkien definisce la distruzione dell’Anello e la caduta di Sauron come la disfatta dell’ultima incarnazione del Male: “We are to see the overthrow of the last incarnation of Evil, the unmaking of the Ring […]” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°131)

- “The Enemy in successive forms is always ‘naturally’ concerned with sheer Domination, and so the Lord of magic and machines; but the problem: that this frightful evil can and does arise from an apparently good root, the desire to benefit the world and others” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°131)

- (J.R.R. Tolkien, Il Signore degli Anelli, Libro 1, cap.II L’Ombra del Passato, pag.103, ISBN 978-88-587-9031-1 © 2020 Giunti Editore S.p.a. / Bompiani). Testo in lingua originale: “‘No!’ cried Gandalf, springing to his feet. ‘With that power I should have power too great and terrible. And over me the Ring would gain a power still greater and more deadly.’ […] Yet the way of the Ring to my heart is by pity, pity for weakness and the desire of strength to do good. Do not tempt me! I dare not take it, not even to keep it safe, unused. The wish to wield it would be too great for my strength. I shall have such need of it.’” (J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring, book 1, ch.2 The Shadow of the Past, pag.61, Ebook Edition © August 2022 ISBN: 9780007322596).

- (J.R.R. Tolkien, Il Signore degli Anelli, Libro 2, cap.VII Lo Specchio di Galadriel, pag.558-559, ISBN 978-88-587-9031-1 © 2020 Giunti Editore S.p.a. / Bompiani). Testo in lingua originale: “In place of the Dark Lord you will set up a Queen. […] Then she let her hand fall, and the light faded, and suddenly she laughed again, and lo! she was shrunken: a slender elf-woman […] ‘I pass the test,’ she said. ‘I will diminish, and go into the West, and remain Galadriel.’” (J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch.7 The Mirror of Galadriel, pag.365-366, Ebook Edition © August 2022 ISBN: 9780007322596).

- “[…] the tale is not really about Power and Dominion: that only sets the wheels going; it is about Death and the desire for deathlessness. Which is hardly more than to say it is a tale written by a Man!” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°203) “It is mainly concerned with Death, and Immortality; and the ‘escapes’: serial longevity, and hoarding memory.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°211)

- Si veda, per esempio, quello che Frodo dice a Sam nella Torre di Cirith Ungol: “The Shadow that bred them can only mock, it cannot make: not real new things of its own. I don’t think it gave life to the orcs, it only ruined them and twisted them; and if they are to live at all, they have to live like other living creatures.” (J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, The Return of the King, book 6, ch.1 The Tower of Cirith Ungol, pag.914, Ebook Edition © August 2022 ISBN: 9780007322596).

- “But certainly Death is not an Enemy! I said, or meant to say, that the ‘message’ was the hideous peril of confusing true ‘immortality’ with limitless serial longevity. Freedom from Time, and clinging to Time. The confusion is the work of the Enemy, and one of the chief causes of human disaster. Compare the death of Aragorn with a Ringwraith.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°208) “Longevity or counterfeit ‘immortality’ (true immortality is beyond Eä) is the chief bait of Sauron – it leads the small to a Gollum, and the great to a Ringwraith.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°212)

- “[…] I am a Christian, and indeed a Roman Catholic, so that I do not expect ‘history’ to be anything but a ‘long defeat’ – though it contains (and in a legend may contain more clearly and movingly) some samples or glimpses of final victory.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°195) “[…] in the Primary Miracle (the Resurrection) and the lesser Christian miracles too though less, you have not only that sudden glimpse of the truth behind the apparent Anankê2 of our world, but a glimpse that is actually a ray of light through the very chinks of the universe about us.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°89)

Laureato in Ingegneria Fisica al Politecnico di Milano dove sta proseguendo la sua carriera come PhD. Fin da bambino è appassionato di Tolkien i cui libri rappresentano per lui uno stimolo e un accompagnamento fondamentali per la vita di tutti i giorni.