di Benedetto Ardini

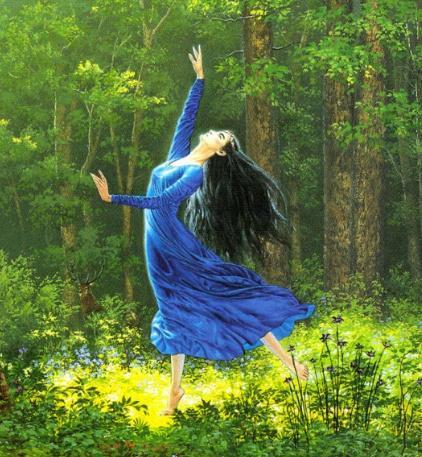

Quando, leggendo i libri di Tolkien, ci immergiamo nella narrazione delle gesta e delle opere degli elfi, nei loro linguaggi, nei loro canti, nelle loro usanze e nelle descrizioni dei loro lineamenti, veniamo catturati dalla meraviglia e dallo splendore di tali creature, descritte dal Professore, esattamente come Beren nel momento in cui sente la voce dell’elfa Lúthien e ne ammira la straordinaria bellezza:

“Vibrava chiara la sua voce, e risonava;

ella cantò, in subitanea estasi,

un canto degli usignoli che aveva appreso

e con elfica magia ella la volse

in una tale avvolgente delizia

che la luna ristette immota nella notte.

E fu questo che Beren udì

e questo vide, senza una parola,

muto per malia, eppur colmo d’un fuoco

che era meraviglia, ch’era desiderio:

opaca gli si fece la mortale mente;

la magia di lei lo avvinse e lo legò1”

Questo passaggio del Lay of Leithian, poema che narra la vicenda dell’amore tra l’uomo mortale Beren e l’elfa Lúthien e che Tolkien scrisse a metà degli anni 19202, è uno degli innumerevoli momenti dell’epopea della Terra di Mezzo in cui il Professore riesce a comunicarci lo splendore proprio degli Elfi. È chiaro che Tolkien sia stato un vero e proprio genio creativo, unico nel suo genere, oltre che un ponte tra la nostra cultura contemporanea e i miti antichi.

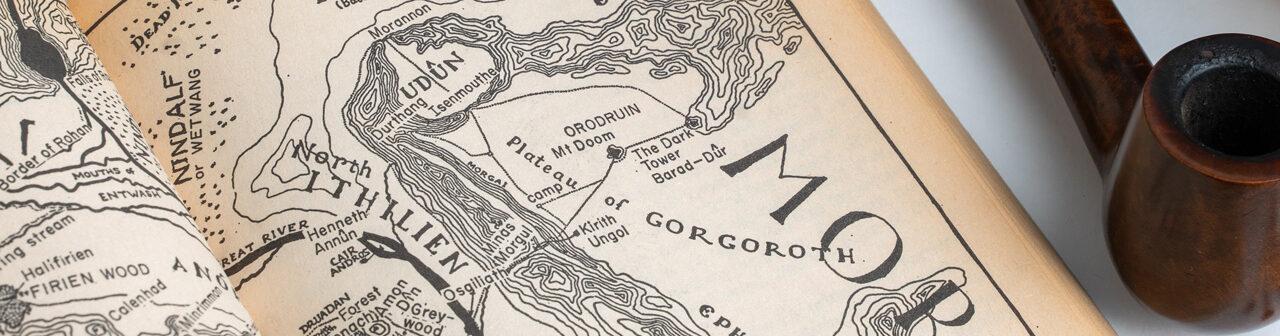

Ma proprio a tal proposito sorge spontanea la domanda: è possibile ritrovare anche solo una parte di questa straordinaria bellezza negli elfi della tradizione antica europea? Dove e quando?Come afferma lo studioso Tom Shippey, l’inizio della presenza degli elfi nelle credenze e nella cultura germanica risale al periodo in cui gli antenati di Inglesi, Germani e Norvegesi parlavano tutti la stessa lingua3: tale momento storico può essere datato tra il 500 a.C ed il 500 d.C.4

Tuttavia, come affermato da Tolkien, poche sono le storie di elfi preservate dall’antica Inghilterra e dalla cultura germanica5 e, contrariamente agli elfi tolkieniani a cui siamo abituati, in tali tradizioni queste creature risultano spesso essere paradossali, contraddittorie e talvolta associate a caratteristiche malvagie6. Nella poesia Antico-Inglese la parola ‘elfo’ ha una connotazione sostanzialmente negativa; infatti nel Beowulf, poema anglosassone scritto attorno all’VIII secolo d.C.7, questo termine è associato a creature malvagie “discendenti da Caino”: troll, giganti e non-morti8.

Nonostante ciò, come sottolineato dallo stesso Tolkien in una sua lettera9, nella tradizione Antico-inglese è anche presente la parola ælfscīne, aggettivo “bello” (letteralemente “splendido come un’elfo”)10, associata ai personaggi biblici di Sara e Giuditta. Questo fatto è molto interessante perché, seppure tra la tradizione originaria germanica degli elfi e i Quendi11 dell’epopea della Terra di Mezzo sembra esserci una distanza abissale12, l’avvenenza attribuita a Sara e Giuditta si avvicina molto ad un concetto di bellezza elfica tolkieniana. Ma dove Tolkien può aver trovato tali riferimenti biblici nella letteratura Antico-inglese?

I testi a cui Tolkien si riferisce sono senz’altro il Genesis A (chiamato anche Older Genesis13) e il Judith che riportano i passaggi che riguardano rispettivamente Sara e Giuditta . Il Genesis A, secondo alcuni studiosi il più antico testo letterario della cultura anglosassone pervenutoci (probabilmente è databile al 700 d.C.)14, appartiene al noto Junius Manuscript (oggi conservato nella Bodleian Library di Oxford) e rappresenta una riscrittura in versi dell’Antico Testamento dalla Creazione fino al sacrificio di Isacco15. Il Judith è un poema antico-inglese di difficile datazione che tratta la storia di Giuditta, la nota eroina giudaica (anche se in questo testo è caratterizzata da elementi cristianizzati16), e del comandante assiro Oloferne. I passaggi nelle due opere in cui troviamo il termine ælfscīne (nelle due forme equivalenti al nominativo femminile ælfscieno e ælfscīnu17) sono i seguenti:

GENESIS A

“Siððan Egypte eagum moton

on þinne wlite wlitan wlance monige,

þonne æðelinga eorlas wenað,

mæg ælfscieno, þæt þu min sie

beorht gebedda, þe wile beorna sum

him geagnian. […]18”

”Quando molti Egiziani orgogliosi con gli occhi

potranno vedere la tua bellezza,

allora i nobili dei principi si aspetteranno che

tu sia la mia radiante moglie, congiunta

avvenente, che alcuni degli uomini desiderano

avere per sé19”

JUDITH

“[…] Þæt wæs þȳ fēorðan dōgore

þæs ðe Iūdith hyne, glēaw on geðonce,

ides ælfscīnu, ǣrest gesōhte.20”

”Accadde che nel quarto giorno

Giuditta, saggia nel pensiero,

donna avvenente, per la prima volta lo visitò21”

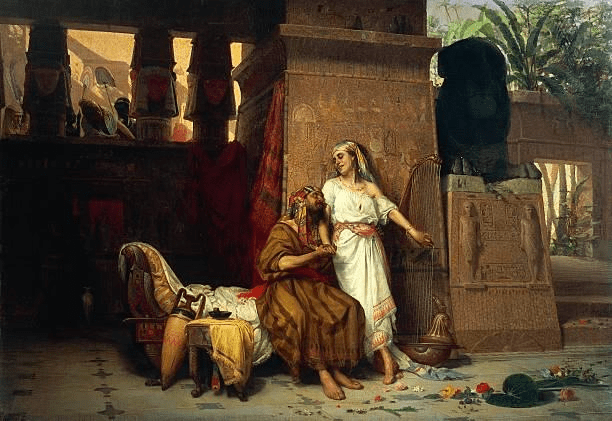

La citazione di Genesis A corrisponde al momento in cui Abramo e Sara, abbandonato il paese di Canaan colpito dalla carestia, vanno in Egitto e il primo anticipa alla moglie che gli Egiziani saranno attratti dalla sua bellezza (Genesi 12,12). La citazione di Judith corrisponde al passaggio in cui, quando Giuditta è ormai al quarto giorno nell’accampamento dei nemici assiri, Oloferne offre un banchetto a cui la donna prende parte (Giuditta 12,10-15). Sarà in questa occasione che il capo degli Assiri, ammaliato dalla bellezza di Giuditta e ubriaco di vino, sprofonderà nel sonno: questo sarà il momento propizio in cui Giuditta lo ucciderà compiendo l’impresa di salvare il popolo di Israele dall’invasore. Interessanti sono le parole “glēaw on geðonce, ides ælfscīnu” che riprendono quasi esattamente l’espressione nell’Antico Testamento con cui Oloferne loda le doti di Giuditta: “graziosa d’aspetto e saggia nelle parole” (Giuditta 11,23).

Dal libro Tolkien’s Library di Oronzo Cilli sappiamo che Tolkien studiò approfonditamente Genesis A e Judith22 e che fu anche relatore di tesi accademiche riguardanti tali testi23. Interessante è il fatto che egli stesse lavorando a delle note su Genesis nel 192824: è proprio attorno a questo periodo che il termine “elfica bella” (elven-fair o elfsheen) cominciò ad essere utilizzato da Tolkien nel suo legendarium. Una prima apparizione è nel canto III del Lay of Leithian scritto nel 192525 dove il termine elven-fair/elven-sheen viene associato all’elfa Lúthien26.

Tuttavia un riferimento diretto al termine anglosassone ælfscīne lo troviamo nell’aggettivo elfsheen (tradotto in elfico Sindarin come eledhwen27)associato per la prima volta al personaggio di Morwen, la madre dell’eroe umano drammatico Túrin Turambar, nei testi degli Annals of Beleriand e Quenta Noldorinwa scritti negli anni 193028. In questo caso il fatto che elfsheen venga associato ad una donna (e non un’elfa) rende un collegamento alle figure di Sara e Giuditta più calzante.

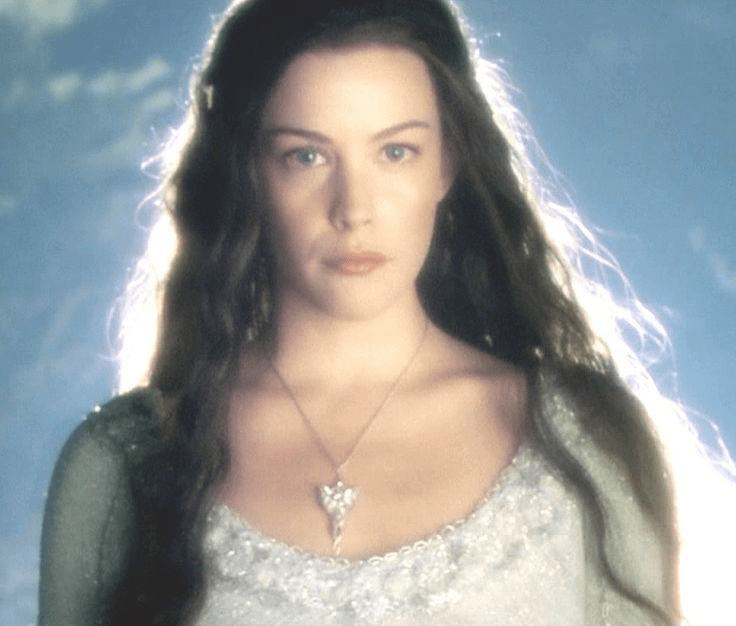

Tolkien riprende il termine elfsheen nel testo di The Lord of the Rings dovetroviamo la resa in elfico Quenya di tale aggettivo associato ad Arwen nelle parole di Aragorn sul monte Cerin Amroth di Lórien, “Arwen vanimelda, namárië!29” (“Arwen bella elfica, addio!30”), e dove è utilizzato nel noto passaggio che richiama la storia di Beren e Lúthien:

“Tinúviel l’elfica bella,

Immortale fanciulla elficamente

Lo avvolse negli umbratili capelli

Che adesso come argento luccicavano.31”

Note bibliografiche

1 Traduzione italiana riportata in J.R.R. Tolkien, La Storia della Terra di Mezzo. I Lai del Beleriand, Canto III, versi 538-539, pag.287, Edizione digitale, ISBN 978-88-587-9548-4. La versione originale è in versi distici ottosillabici: “Then clearly thrilled her voice and rang; / with sudden ecstasy she sang / a song of nightingales she learned / and with her elvish magic turned / to such bewildering delight / the moon hung moveless in the night. / And this it was that Beren heard, / and this he saw, without a word, / enchanted dumb, yet filled with fire / of such a wonder and desire / that all his mortal mind was dim; / her magic bound and fettered him” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.3, The Lays of Beleriand, III. The Lay of Leithian, Canto III, pag.183, Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2019 ISBN: 9780007348206)

2 Il Lay of Leithian fu scritto da Tolkien tra il 1925 e il 1931 e, in particolare, il Canto III di cui fa parte il passaggio citato è stato scritto molto probabilmente nel 1925. Afferma Christopher Tolkien: “My father wrote in his diary that he began ‘the poem of Tinúviel’ during the period of the summer examinations of 1925 […] and he abandoned it in September 1931 […] when he was 39.” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.3, The Lays of Beleriand, III. The Lay of Leithian, Canto III, pag.183, Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2019 ISBN: 9780007348206)

3 “The wide distribution of the word in space and time proves that belief in such creatures, whatever they were, was once both normal and immemorially old, going back to the times when the ancestors of Englishmen and Germans and Norwegians still spoke the same tongue.” (Tom Shippey, The Road to Middle-earth: How J.R.R. Tolkien created a new mithology, ch. 3 The Burgeois Burglar, pag. 65, Kindle Edition)

4 Da studi linguistici si sa che esisteva una certa affinità linguistica tra diversi popoli germanici prima del 500 d.C. (si veda ad esempio Bizzocchi, Aldo Luiz. “Revising the History of Germanic Languages: The Concept of Germance.” Linguistics 9.1 (2021): 1-5.). Tale “unità” linguistica è quello che i filologi individuano come proto-Germanico che si diffuse a partire dal 500 a.C. “Proto-Germanic […] is unlikely to have been spoken before about 2,500 years ago (c.a. 500 BC). […] The definition of ‘Proto-Germanic’ […] is determined by the methodology of comparative linguistics: it is the last common ancestor of the adequately attested Gmc languages, as reconstructed from those attested languages by application of the comparative method.” (Don Ringe, From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. Volume 1, ch.3 The Development of Proto-Germanic, 3.1 Introduction, pag.84, ISBN 978-0-19-879258-1)

5 “There are no songs or stories preserved about Elves or Dwarfs in ancient English, and little enough in any other Germanic language. Words, a few names, that is about all. I do not recall any Dwarf or Elf that plays an actual part in any story save Andvari in the Norse versions of the Nibelung matter.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°236)

6 “[…] Tolkien must soon have come to the conclusion that all linguistically authentic accounts of the elves, from whichever country they came, agreed on one thing: that the elves were in several ways paradoxical. For one thing, people did not know where to place them between the polarities of good and evil.” (Tom Shippey, The Road to Middle-earth: How J.R.R. Tolkien created a new mithology, ch. 3 The Burgeois Burglar, pag. 65-66, Kindle Edition)

7 Si veda Colin Chase, The Dating of Beowulf, ISBN 0-8020-7879-6

8 “In all Old English poetry ‘elves’ (ylfe) occurs once only, in Beowulf, associated with trolls, giants, and the Undead, as the accursed offspring of Cain.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°236). Nella sua traduzione del Beowulf, Tolkien rese la parola ylfe (‘elves’) con ‘goblins’: “evil broods were born, ogres and goblins and haunting shapes of hell, and the giants too, that long time warred with God – for that he gave them their reward.” (J.R.R. Tolkien, Beowulf, verses 90-92, pag.16, Ebook Edition)

9 “[…] the occurrence of aelfsciene ‘elven-fair’ applied to Sarah and Judith!” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°236)

10 Il termine è riportato anche da Tom Shippey: “Ælfscýne is an approbatory Anglo-Saxon adjective for a woman, ‘elf-beautiful’. Fríð sem álfkona, said the Icelanders, ‘fair as an elf-woman’.” (Tom Shippey, The Road to Middle-earth: How J.R.R. Tolkien created a new mithology, ch. 3 The Burgeois Burglar, pag. 66, Kindle Edition). La traduzione riportata nei dizionari Old English è quella di “bella come una fata”: “ælfscīne adj. beautiful as a fairy nsf ælfscinu.” (Mitchell, Bruce; Robinson, Fred C.. A Guide to Old English, pag. 420, Wiley. Edizione del Kindle). La parola contiene il verbo scīnan che significa “splendere” (‘shine’) (Mitchell, Bruce; Robinson, Fred C.. A Guide to Old English, pag.54, Wiley. Edizione del Kindle).

11 Quendi è il termine utilizzato da Tolkien per riferirsi a tutte le tipologie di Elfi nel suo legendarium: questo era il nome che gli elfi davano a loro stessi e che significa “coloro che parlano con voci” (si veda The Silmarillion, ch.3 Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor, pag.45, Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2011 ISBN: 9780007322565)

12 “The gap between that and, say, Elrond or Galadriel is not bridged by learning.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°236)

13 “The text of the poem as it is preserved in the Junius Manu-script is a composite of the work of at least two different poets. The main body of the text, extending from l. 1 to l. 234 and from l. 852 to the end is commonly known as Genesis A, or the Older Genesis. The passage from l. 235 to l. 851 is known as Genesis B, or the Later Genesis.” (Krapp, George Philip. Revival: The Junius Manuscript, X. Unity of the Poems in the Manuscript, 1.Genesis, 1931, Edizione Kindle)

14 “No direct evidence is available for dating Genesis A, the Older Genesis, although the end of the seventh or the beginning of the eighth century is generally accepted as a probable time for the original composition-of the poem. Sarrazin has endeavored, on the evidence of meter, to show that Genesis A is older than BEOWULF and, in fact, the oldest English literary monument. Klaeber, on the evidence of apparent borrowings, also decided that Genesis A was older than BEOWULF. […] The language of Genesis A as it is preserved is, in general, West Saxon of a later period than 700, but there occur in the recorded text of the poem a number of forms which are commonly accounted for as indications of an original Anglian dialect in which the poem was composed and which were blurred over when the was transcribed into West Saxon. If the poem was written in the north of England, about the year 700, time and theme fit so exactly the description of Cdmon as poet given by Bede that the ascription of the poem to Caodmon might seem to be beyond cavil.” (Krapp, George Philip. Revival: The Junius Manuscript, X. Unity of the Poems in the Manuscript, 1.Genesis, 1931, Edizione Kindle)

15 “[…] versification of the first book of the Old Testament, though it carries the story only from the Creation to the sacrifice of Isaac […]” (Krapp, George Philip. Revival: The Junius Manuscript, X. Unity of the Poems in the Manuscript, 1.Genesis, 1931, Edizione Kindle)

16 “The Jewish heroine is not only heroicized in the traditional Germanic way but is also Christianized: she prays to the Holy Trinity and names the Son of God.” (Mitchell, Bruce; Robinson, Fred C.. A Guide to Old English, 20.Judith, pag.373, Wiley. Edizione del Kindle). Questo fatto della cristianizzazione di Giuditta viene sottolineato anche dallo stesso Tolkien: “Avoidance of obvious anachronisms (such as are found in Judith, for instance, where the heroine refers in her own speeches to Christ and the Trinity) […]” (J.R.R. Tolkien, The Monsters and the Critics, Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, pag.45, note 20, Ebook Edition © October 2012 ISBN: 9780007375905)

17 Sul fatto che a volte si trovi ie e a volte ī si veda: “But by King Alfred’s time ie was pronounced as a simple vowel (monophthong), probably a vowel some-where between i and e; ie is often replaced by i or y […]” (Mitchell, Bruce; Robinson, Fred C.. A Guide to Old English, pag.30, Wiley. Edizione del Kindle). Infatti Tom Shippey riporta il termine con ȳ: “Ælfscýne is an approbatory Anglo-Saxon adjective for a woman, ‘elf-beautiful’.” (Tom Shippey, The Road to Middle-earth: How J.R.R. Tolkien created a new mithology, ch. 3 The Burgeois Burglar, pag. 66, Kindle Edition). Sul fatto che si trovi anche la forma femminile con la -o finale è naturale se prendiamo in esame un parola come niht-waco, “osservatrice della notte” con waco che deriva dal verbo wacian, “osservare, guardare”: lo stesso possiamo pensare per il verbo scīnan, “splendere” che diventa l’aggettivo femminile scīno (si veda Mitchell, Bruce; Robinson, Fred C.. A Guide to Old English, Wiley. Edizione del Kindle alle pag.78, 561, 601).

18 Krapp, George Philip. Revival: The Junius Manuscript, X. Unity of the Poems in the Manuscript, 1.Genesis, verses 1824-1829, 1931, Edizione Kindle

19 I riferimenti per la traduzione sono tutti al libro Mitchell, Bruce; Robinson, Fred C.. A Guide to Old English, Wiley. Edizione del Kindle: Siððan, avv. “quando” (pag.570); Egypte, m. pl. “Egiziani”; eagum, dat.plur. di ēage, “occhio” (pag. 35) (il dativo può avere il ruolo di strumentale, pag.31); moton, 3 pers.plur. pres. di mōtan, “potere, avere la possibilità” (pag.536); on, avv. “su” (pag.546); þinne, agg. “tuo” (pag.592); wlite, “bellezza” (pag.615); wlitan, “guardare, ammirare” (pag.615); wlance, agg. nom.masch.plur. “splendido, orgoglioso” (pag.615); monige,nom.plur. di maniġ, “molti, una grande quantità/numero” (pag.527); þonne, avv. “allora” (pag.90); æþelinga, gen.plur. di æþeling, “principe” (pag.422); eorlas, nom.plur. di eorl, “nobleman” (pag.464); wenað, pres. ind. di wēnan, “pensare, aspettarsi” (pag.607) (il pres. ind. plur. È formato con -að, pag.148); mæg, “congiunto/a” (pag.529); þæt, avv “that” (es. pag.86); þu, pron. “tu” (pag.595); mīn, agg.poss. acc.sing.femm. “mia” (pag.534); sīe, cong. 2 pers. di bēon, “essere” (pag.429); beorht, agg. nom. sing. femm. “radiante, splendente, chiara”; gebedda, nom. sing. femm. “congiunta, compagna di letto” (https://bosworthtoller.com/013599); þe, particella non declinabile “che” (pag.589); wile, 3 pers. sing. pres. ind. di willan, “desiderare” (pag.611), beorna, gen. plur. di beorn, “uomo, guerriero” (pag.430); sum, pron. nom. sing. masch. “una parte, alcuni” (pag.577); him, “per sé” dat. sing. masch. di hē, hēo, hit, “egli” (pag.497) (vedi pag. 100 “for himself”); geagnian, “possedere” (https://bosworthtoller.com/13403).

20 Mitchell, Bruce; Robinson, Fred C.. A Guide to Old English, pag.54, verses 12-14, Wiley. Edizione del Kindle

21 I riferimenti per la traduzione sono tutti al libro Mitchell, Bruce; Robinson, Fred C.. A Guide to Old English, Wiley. Edizione del Kindle: Þæt wæs . . .þæs ðe,“accadde che” (pag.387); þȳ,strumentale di se, þæt, sēo, pron. dim. “che”; fēorðan, strumentale sing. masch. di fēorða, agg. num. “quarto”; dōgore, strumentale di dōgor, “giorno” (pag.452) (lo strumentale può esprimere il complemento di tempo, pag.121); hine, pron. acc. “lui, egli” (pag.95); glēaw, agg. nom-masch. “saggio, lungimirante” (pag.489); geðonce, dat. sing. di ġeðonc, masch. “thought” (pag.593); ides, nom. sing. femm. “woman” (pag.514); ǣrest, avv. “prima, per la prima volta” (pag.421); gesōhte, pass. 3 pers. sing. di ġesēċan, “cercare, visitare” (pag.564)

22 Lista di libri inerenti all’argomento che Tolkien consultò: • 574. Dobbie, Elliott Van Kirk. Beowulf, and Judith. Series: The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records, 4. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1953. • 793. Gollancz, Israel (Edited by). The Cædmon Manuscript of Anglo-Saxon Biblical Poetry, Junius XI in the Bodleian Library. London: Published for the British academy by H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1927. • 1151. Judith. [Old English poem] • 1226.______ (Edited by). The Junius Manuscript. Series: The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records, 1. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1931. • 2087. ______. ‘Zu Codex Junius XI’. Beiträge zur Geschichte der älteren Deutschen Litteratur, Vol. X. Bonn: E. Weber, 1855, pp. 195-99. (Cilli, Tolkien’s Library, Tolkien’s Library, ISBN-13: 978-1-911143-68-0)

23 Le tesi in questione riguardano il Junius Manuscript e sono intitolate “The History of Old English and Old Norse Studies in England from the Time of Junius till the End of the Eighteenth Century.” e “Studies in the treatment of Old Testament themes in the poems of MS. Junius 11, Pt. 1.” (si veda Cilli, Tolkien’s Library, J.R.R. Tolkien: Supervisor and Examiner: 1929-1960, n°2 pag.1010 e n°39 pag.1022, ISBN-13: 978-1-911143-68-0)

24 “Tolkien’s copy of Studien zu den Skalden des 9. und 10. Jahrhunderts (1928) by Konrad Reichardt, contains a page of notes on the verso of Tolkien’s dining expenses from Pembroke College during the week of 29 November 1928; the notes refer to the Genesis and Exodus poems – Old English poetry which Tolkien would used while working on Cynewulf’s Crist.” (Cilli, Tolkien’s Library, Tolkien’s Library, pag.234, ISBN-13: 978-1-911143-68-0)

25 “Canto III was in being by the autumn of 1925” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.3, The Lays of Beleriand, III. The Lay of Leithian, Commentary on Canto IV, pag.236, Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2019 ISBN: 9780007348206).

26 “half elven-fair and half divine” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.3, The Lays of Beleriand, III. The Lay of Leithian, Canto III, verse n°493, pag.211, Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2019 ISBN: 9780007348206). “Thereafter on a hillock green / he saw far off the elven-sheen / of shining limb and jewel bright / often and oft on moonlit night” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.3, The Lays of Beleriand, III. The Lay of Leithian, Canto III, verse n°709-712, pag.217, Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2019 ISBN: 9780007348206). “O elven-fairest Lúthien what wonder moved thy dances then?” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.3, The Lays of Beleriand, III. The Lay of Leithian, Canto III continued, verse n°104, pag.421, Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2019 ISBN: 9780007348206). Il termine elven-fair/elven-sheen non è presente nella prima versione del racconto di Beren e Lúthien, il Tale of Tinúviel, dove troviamo solo fair elfin maiden: “This was a great sorrow to Beren, who would not leave those places, hoping to see that fair elfin maiden dance yet again, and he wandered in the wood growing wild and lonely for many a day and searching for Tinúviel.” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.2, The Book of Lost Tales: Part II, I.The Tale of Tinúviel, pag.11, Ebook Edition © April 2010 ISBN: 9780007348190).

27 “The Grey-elven (Sindarin) forms should have been êl, pl. elin; and eledh (pl. elidh). But the latter term passed out of use among the Grey-elves (Sindar) who did not go over Sea; though it remained in some proper-names as Eledhwen, ‘Elven-fair’.” (Humphrey Carpenter, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, letter n°211)

28 Per quanto concerne il Quenta Noldorinwa si veda: “Morwen now gains the name ‘Elfsheen’ […]” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.4, The Shaping of Middle-earth, ch. III The Quenta, Commentary on the Quenta, 9, pag.217, Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2018 ISBN: 9780007348213). Per quanto concerne gli Annals of Beleriand si veda: “Their wives and children were captured or slain by Morgoth, save Morwen Eledwen Elfsheen (daughter of Baragund) and Rían (daughter of Belegund) […]” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.4, The Shaping of Middle-earth, ch. VII The Earliest Annals of Beleriand, pag.391, note 24, Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2018 ISBN: 9780007348213). Per la datazione dei testi citati si veda l’introduzione di Christopher Tolkien: “This book brings the ‘History of Middle-earth’ to some time in the 1930s: the cosmographical work Ambarkanta and the earliest Annals of Valinor and Annals of Beleriand, while later than the Quenta Noldorinwa – the ‘Silmarillion’ version that was written, as I believe, in 1930 […]” (The History of Middle-earth, vol.4, The Shaping of Middle-earth, Preface, pag.8, Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2018 ISBN: 9780007348213).

29 The Lord of the Rings, vol.I The Fellowship of the Rings, book 2, ch.VI Lothlórien, pag.352, Ebook Edition © August 2022 ISBN: 9780007322596

30 Parma Eldalamberon n°17, pag.56-58

31 Traduzione presa da J.R.R. Tolkien, Il Signore degli Anelli, Libro 1, cap.XI Un Coltello nel Buio, pag.301, ISBN 978-88-587-9031-1 © 2020 Giunti Editore S.p.a. / Bompiani. Il testo originario è: “Tinúviel the elven-fair, / Immortal maiden elven-wise, / About him cast her shadowy hair / And arms like silver glimmering.” (The Lord of the Rings, vol.I The Fellowship of the Rings, book 1, ch.XI A Knife in the Dark, pag.192, Ebook Edition © August 2022 ISBN: 9780007322596)

Laureato in Ingegneria Fisica al Politecnico di Milano dove sta proseguendo la sua carriera come PhD. Fin da bambino è appassionato di Tolkien i cui libri rappresentano per lui uno stimolo e un accompagnamento fondamentali per la vita di tutti i giorni.